Every now and then, India’s linguistic debate resurfaces like an old ghost in new attire. The latest episode unfolded in Tamil Nadu, where the state budget replaced the rupee symbol (₹) with ‘Rs’—a subtle yet sharp message rejecting what many see as the imposition of Hindi through symbols of national identity. This brings us back to the enduring question: Should Hindi be India’s national language? And if so, at what cost?

The Constitutional Reality: Hindi as an Official Language, Not National

First, let’s get our definitions straight. India has no national language. Article 343 of the Constitution designates Hindi in Devanagari script as an “official language” alongside English. It is not the “national” language—an often-repeated misconception. The Eighth Schedule recognizes 22 languages, reflecting India’s linguistic diversity. While Hindi enjoys prominence due to its wide usage, it does not legally trump other languages.

A national language, by definition, represents the cultural and linguistic identity of a country. But can one language define a nation as diverse as India? The answer lies in our history. In 1965, when the government attempted to replace English with Hindi as the sole official language, protests erupted across non-Hindi-speaking states, particularly in Tamil Nadu, where students set themselves on fire in opposition. The resistance was so strong that the government was forced to back down, retaining English as an associate official language indefinitely.

The Numbers Game: Does Hindi Deserve National Status?

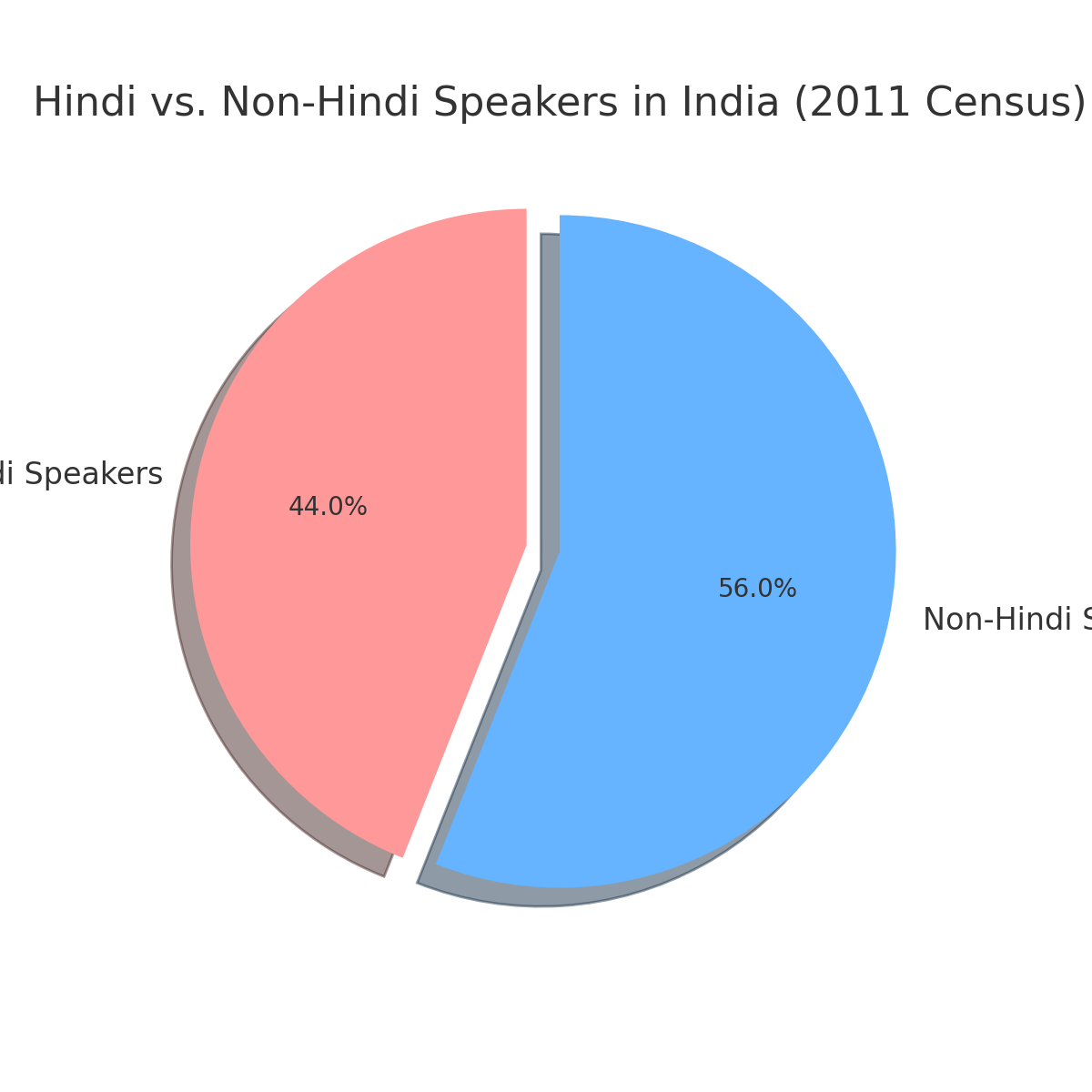

Proponents of Hindi as a national language argue that it is the most spoken language in India. The 2011 Census data shows that nearly 44% of Indians identify Hindi as their mother tongue. But here’s the catch—this includes several dialects such as Bhojpuri, Maithili, and Rajasthani, which are linguistically distinct. If we separate them, the number of native Hindi speakers drops significantly.

More importantly, over 55% of Indians do not speak Hindi as their first language. In states like Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, and Kerala, Hindi is a secondary or tertiary language, often spoken out of necessity rather than preference. Should a language that less than half the population speaks as a mother tongue be imposed as a national identity?

Economic and Political Implications: A Language of Power?

There’s an economic argument, too. The dominance of Hindi in governance and job opportunities—especially in government exams—creates an uneven playing field. A Tamil-speaking aspirant in Chennai must learn Hindi to access opportunities in Delhi, but the reverse is rarely true. This linguistic asymmetry fuels resentment and deepens regional divides.

In contrast, English, despite its colonial baggage, remains the neutral bridge. It is the language of global business, higher education, and technology. Unlike Hindi, English does not belong to any single Indian state, making it an acceptable common denominator.

The Cultural Pushback: Tamil Nadu’s Symbolic Resistance

Tamil Nadu’s recent move to replace the rupee sign with ‘Rs’ in its budget documents is more than just an accounting decision—it’s a political statement. The rupee sign (₹), designed in 2010, incorporates elements of Devanagari and Latin scripts, subtly nodding to Hindi. Tamil Nadu, with its long-standing opposition to Hindi imposition, has taken a small but symbolic step to assert linguistic autonomy.

This resistance is not new. The Dravidian movement in Tamil Nadu has historically opposed Hindi’s imposition, leading to policies that prioritize Tamil in education, governance, and even cinema. Over time, this sentiment has only intensified, with recent controversies over central government directives promoting Hindi in official communications further deepening regional anxieties.

Does India Need a National Language?

One might argue that a national language fosters unity. But history tells us otherwise. Pakistan’s imposition of Urdu on Bengali speakers in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) led to violent protests and, ultimately, the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. Sri Lanka’s decision to declare Sinhala the sole official language in 1956 fueled ethnic tensions that spiraled into a civil war lasting nearly three decades.

India’s strength has always been its plurality. Unlike France, where linguistic purity is enforced, or China, where Mandarin is aggressively promoted at the cost of regional languages, India thrives in its linguistic chaos. From Bollywood’s Hinglish dialogues to Kerala’s English-Tamil-Malayalam fusion, we don’t need a national language to feel like a nation. Our linguistic diversity is not a weakness; it is a defining characteristic.

Embracing Multilingualism

If the goal is national unity, the answer is not to push Hindi but to embrace multilingualism. India already follows a three-language formula—students in most states learn their regional language, Hindi, and English. Yet, this policy is often applied unevenly, with Hindi-speaking states resisting the learning of a South Indian language. Why should the burden of bilingualism always fall on non-Hindi speakers?

Instead of imposing Hindi, we should promote language diversity in practical ways. Government recruitment should reward multilingual proficiency, not just Hindi. Regional languages should be encouraged in higher education, alongside English and Hindi, ensuring that linguistic diversity does not become a career disadvantage.

A Language of the People, Not the Nation

The idea of Hindi as a national language is neither constitutional nor practical. It is a political debate, often revived for electoral gains, but one that does little to unite India. Tamil Nadu’s decision to tweak the rupee symbol is just one instance of the ongoing pushback against linguistic centralization. Rather than forcing Hindi down people’s throats, India should celebrate its linguistic diversity. After all, true unity lies not in uniformity, but in the ability to thrive in differences. That is what makes India, India.